Is the Chips Act Achieving Its Objectives?

The CHIPS Act has laid the foundation for the U.S. to join the chips race

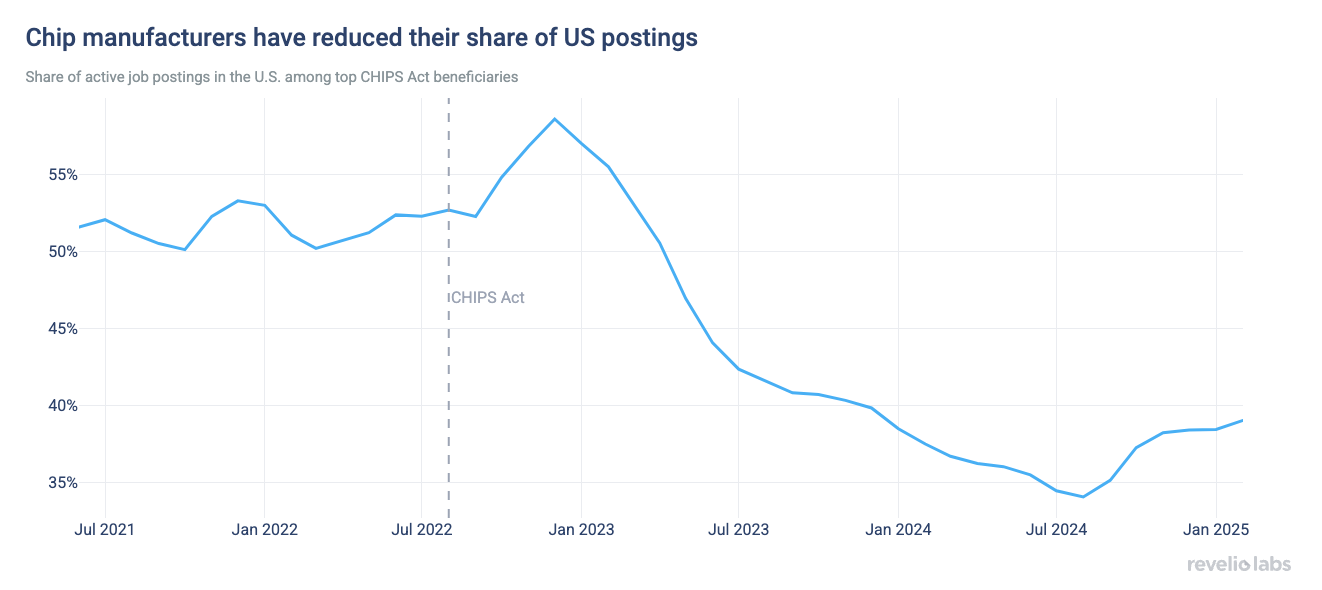

Following the passage of the CHIPS Act, the U.S. share of job postings among major beneficiary companies initially rose but has since declined, raising questions about the long-term impact of the legislation on domestic semiconductor manufacturing.

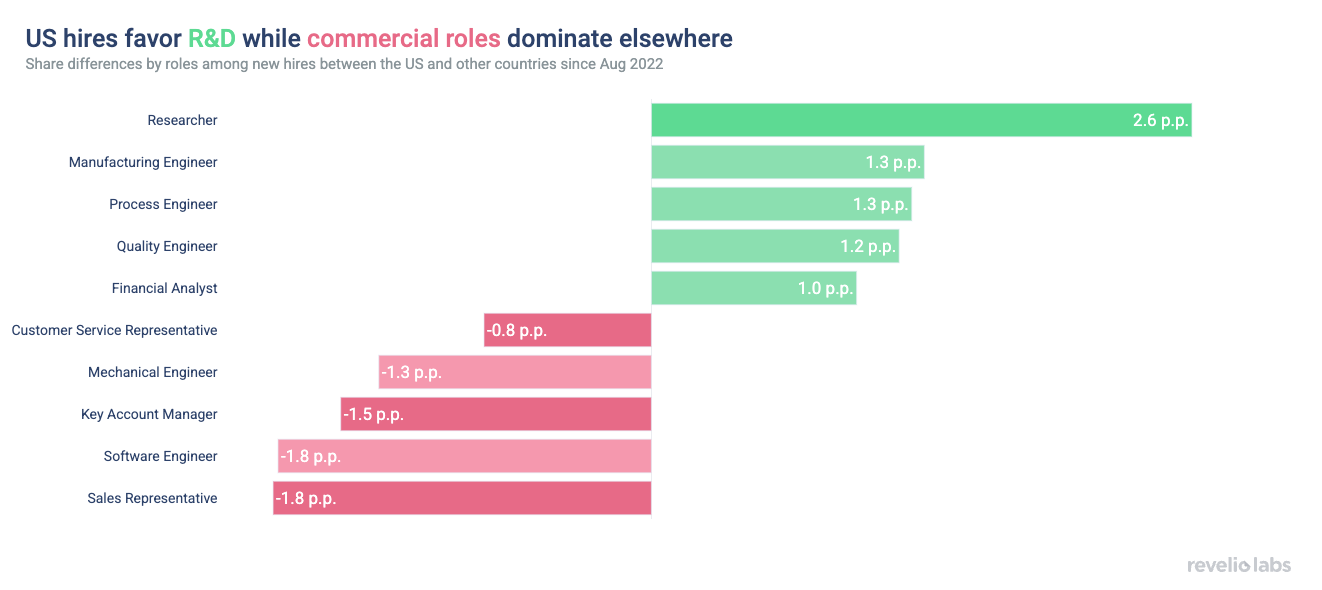

In the U.S., however, new hires since the CHIPS Act have primarily been highly skilled researchers and manufacturing engineers, many with doctoral degrees, reflecting a focus on R&D and early-stage manufacturing and laying the groundwork for future production.

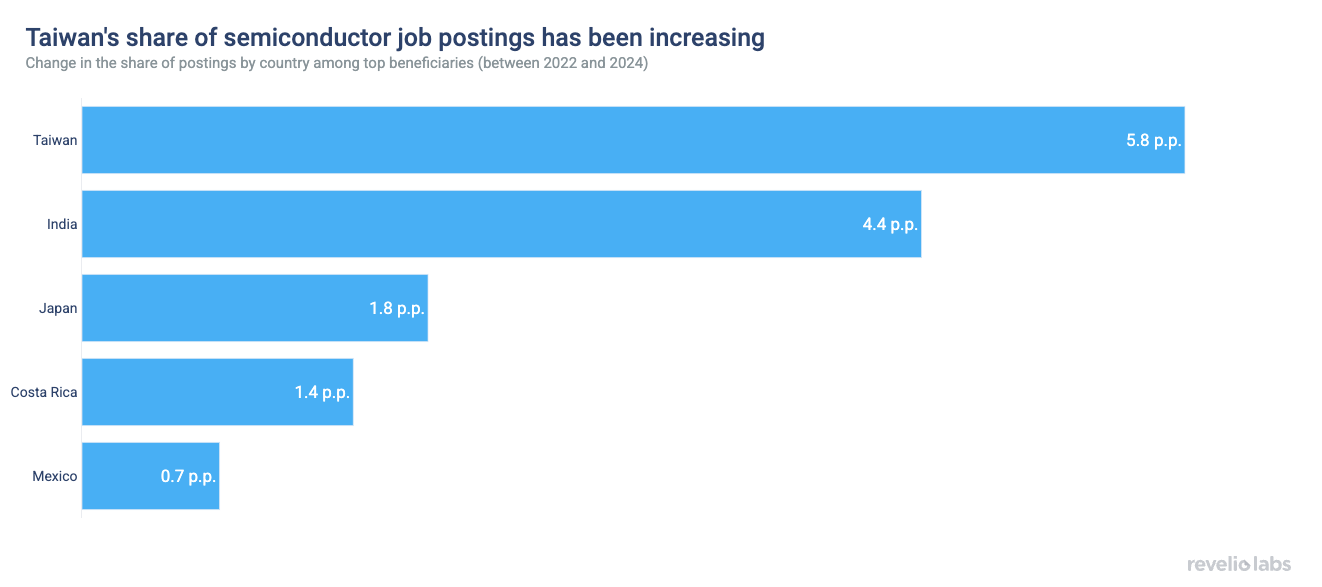

Taiwan is capturing a growing share of postings, driven partly by TSMC’s decision to expand production at home to meet surging AI-related demand. TSMC is capitalizing on the local labor force that is more closely aligned with current hiring needs, despite ongoing investments in U.S. facilities.

The CHIPS and Science Act, enacted in 2022, was designed to bolster U.S. semiconductor manufacturing, research, and workforce development. In previous newsletters, we noted an initial uptick in the share of new job postings in the U.S. following the announcement. At the same time, we highlighted the industry’s ongoing challenges in meeting its ambitious goals—particularly the growing talent shortage across engineering, manufacturing, and technical roles. Recently, President Trump criticized the effectiveness of the CHIPS Act and issued an executive order to establish a new oversight entity—the United States Investment Accelerator—signaling a potential shift in how future semiconductor investments may be managed. In this week’s newsletter, we revisit our earlier analysis to assess how the CHIPS Act is currently impacting the U.S. labor market and whether it is succeeding in bringing semiconductor jobs back to American soil.

Since the passage of the CHIPS and Science Act, companies including Intel, Micron, GlobalFoundries, Polar Semiconductor, TSMC, Samsung, BAE Systems, and Microchip Technology have been among the largest beneficiaries of the legislation. Using Revelio Labs’ COSMOS job postings data, we observe an initial rise in the share of U.S.-based postings for these firms following the Act’s announcement. However, that share has since declined, raising questions about the long-term effectiveness and sustainability of the CHIPS Act on job creation and its ability to anchor high-skilled semiconductor jobs in the U.S. amidst intensifying global competition.

TSMC stands out among companies with the largest decline in U.S.-based job posting share, which fell by 35 percentage points between 2022 and 2024. Unsurprisingly, Taiwan gained share over the same period, drawing postings away from the U.S. by nearly 6 percentage points.

According to a recent report from the Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA), global semiconductor sales reached $627.6 billion in 2024—an increase of 19.1% from $526.8 billion in 2023. Given the long timelines required to build new fabs, companies like TSMC are prioritizing expansion within existing facilities. Although TSMC is investing heavily in new plants in Arizona, it is simultaneously ramping up production at home in Taiwan to meet surging demand driven by the AI boom. Meanwhile, India has also gained share from the U.S. in recent years, supported by significant government investment through its CHIPS initiative—the India Semiconductor Mission.

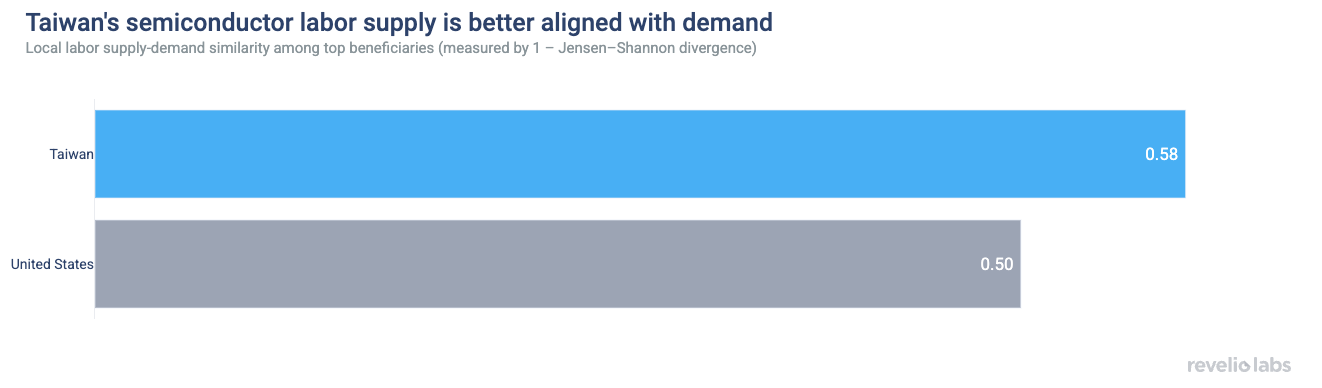

Another reason Taiwan may be gaining a greater share of job postings is that its local labor force is better aligned with current hiring demand, making it easier for companies to fill open roles. To measure this alignment, we compared the distribution of advertised roles (demand) with that of the existing workforce (supply) using a Jensen–Shannon–based similarity score, calculated as 1 minus the divergence score—where higher values indicate a closer match. Taiwan scores 0.58, while the United States scores 0.50, suggesting that Taiwan’s semiconductor labor supply is closely aligned with current hiring needs. This finding is consistent with previous evidence of a talent shortage in the U.S. semiconductor sector. Taiwan’s stronger alignment enables companies to staff fabrication facilities more efficiently, reinforcing its attractiveness for future semiconductor investment.

Although manufacturers are ramping up production at their existing fabs, this does not mean that hiring in the U.S. is slowing down. In fact, since the passage of the CHIPS Act, U.S. hiring has shown a clear prioritization of certain roles. When we compare the composition of new hires between the U.S. and the rest of the world, we find that U.S.-based hiring has been disproportionately focused on researchers and manufacturing engineers. In contrast, hiring in other countries has leaned more heavily toward administrative and commercial roles, such as sales representatives and account managers. This suggests that U.S. hiring has concentrated on R&D and early-stage manufacturing planning—the foundational phases of semiconductor production—while international hiring has been more oriented toward business operations and customer-facing functions.

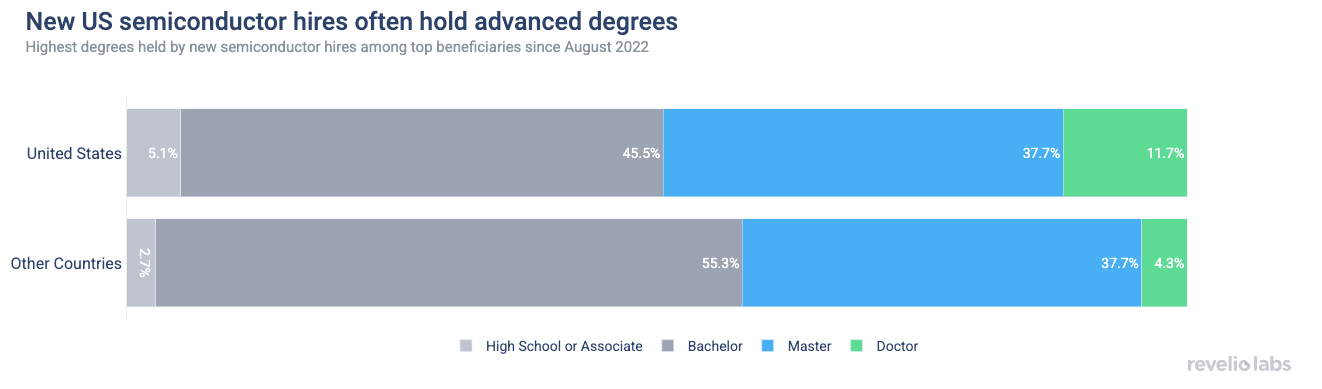

It’s also not surprising that new hires in the U.S. are more likely to hold advanced degrees. Roughly 12% of U.S. new hires have a doctoral degree—more than 7 percentage points higher than the share in other countries. Although shortages in skilled manufacturing labor remain a persistent challenge, companies appear to face fewer difficulties hiring individuals with research backgrounds and advanced degrees. This trend reflects the strength of the U.S. higher education system, which continues to produce a steady pipeline of highly trained scientists and researchers, aligning with the R&D-oriented hiring surge seen since the CHIPS and Science Act came into force.

Overall, the CHIPS and Science Act has jump-started U.S. hiring for research and process-development roles, yet it has not fully anchored the broader production workforce the industry ultimately needs. Posting momentum is already swinging back toward Taiwan—whose labor force more closely mirrors firms’ current needs—and toward fast-growing hubs such as India. Meanwhile the U.S. higher education system faces mounting challenges—from declining international enrollment to reduced public funding—which could undermine one of the country’s key advantages in the semiconductor sector: its ability to supply highly innovative R&D talent. If left unaddressed, these pressures may weaken the pipeline of advanced-degree holders that has thus far supported the R&D-focused hiring momentum spurred by the CHIPS Act. Moreover, reduced investment in higher education can have a broader trickle-down effect, limiting resources for community colleges, certification programs, and trade schools that are critical for training the frontline technicians and manufacturing workers essential to scaling semiconductor production. To secure a durable share of the next wave of semiconductor growth, policymakers and firms must reinforce both ends of the talent spectrum—investing to keep top researchers onshore while expanding practical training pathways that can translate breakthroughs into volume production.