Brexit: Goodbye Europe, Hello Global Workforce

Brits now make up less of the country’s workforce

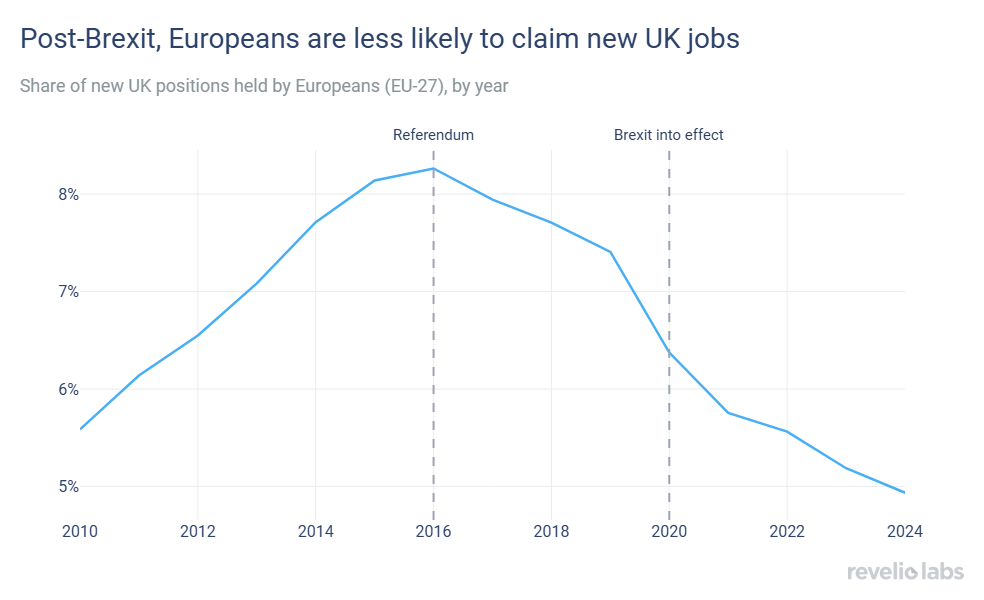

The share of Europeans (from EU-27 states) starting new positions in the UK has sharply dropped after Brexit went into effect in January 2020: In 2016, more than 8% of new positions in the UK were filled by Europeans; by 2024, this figure has declined to approximately 5%.

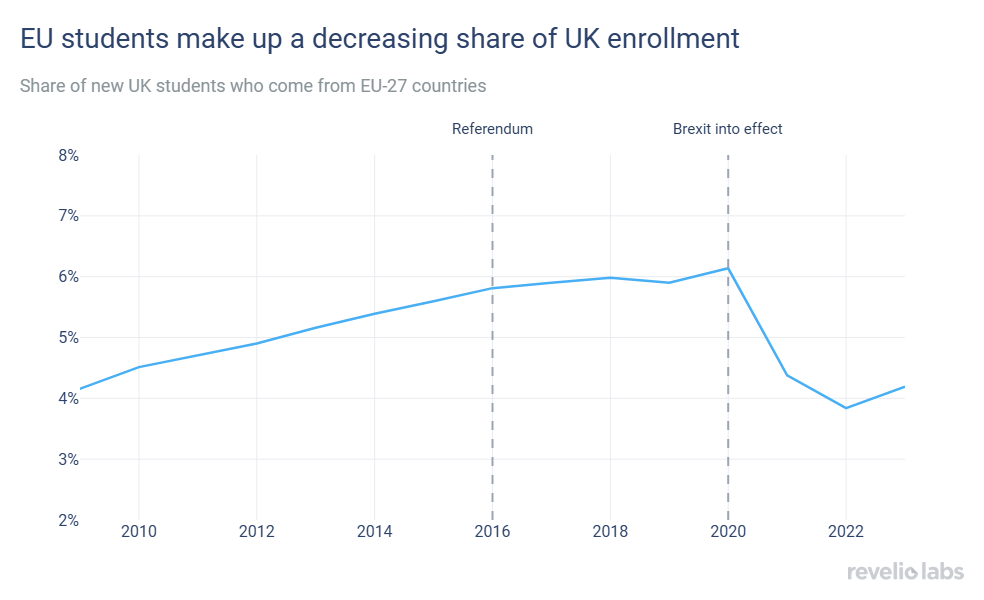

This trend is not limited to participation in the workforce: The UK university student body is also increasingly less European.

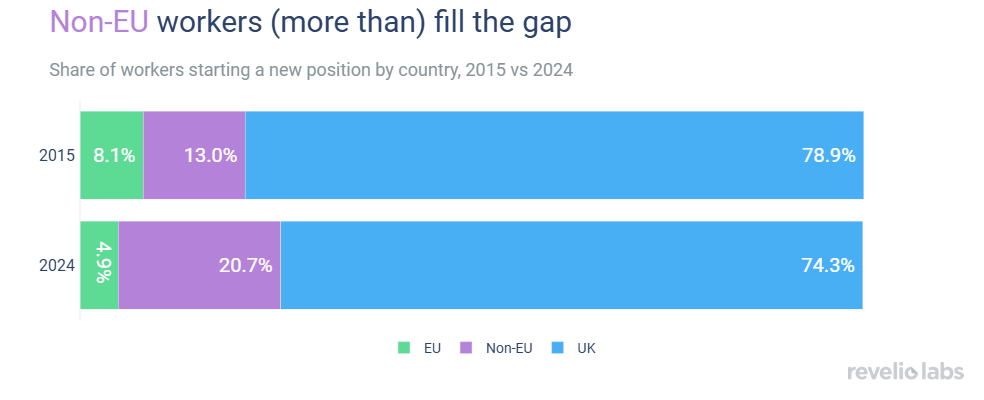

The shift away from Europeans does not necessarily mean more opportunities for the British: Post-pandemic, an increase in migration from the rest of the world has more than compensated for the decline in European immigration.

January 2025 marks five years since the United Kingdom’s departure from the European Union—a pivotal decision that has had lasting effects on the nation’s economy and workforce. This milestone provides an opportunity to evaluate how Brexit has transformed the UK labor market and examine its broader implications for industries and talent flows. In today’s newsletter, we explore the changes that have unfolded since the UK’s separation from the EU.

We use Revelio Labs workforce data to identify Europeans (from EU-27 member states) on the basis of their professional and educational history. We find that the share of Europeans starting new positions in the UK has sharply dropped after Brexit went into effect in January 2020: In 2016, more than 8% of new positions in the UK were filled by Europeans; by 2024, this figure has declined to approximately 5%. This trend is further reflected in cross-border mobility. Among workers based in Europe who changed jobs, 1 in 66 chose the UK as their next destination in 2015. By 2024, this figure had dropped to almost 1 in 200, suggesting the UK may have become less attractive—or harder to access—for European talent after Brexit.

This shift extends beyond the workforce to education. Following nearly a decade of steady growth, the share of EU students enrolling in UK programs plummeted after Brexit took effect in 2020, returning to early 2010s levels. In contrast, student mobility within other European countries has continued to rise, with the share of foreign EU students growing consistently despite the challenges of the pandemic.

Both trends reflect the increased difficulties that European citizens now face when moving to the UK. Pre-Brexit, any EU citizen could freely move, work, and study in the country, thanks to the freedom of movement principles that are at the founding core of the European Union. As of 2024, most Europeans looking to move to the UK need to obtain a work or study visa, which requires sponsorship from employers in most cases. Additionally, prior to Brexit, EU students were typically eligible for "home" fee status, meaning they paid the same tuition fees as UK students and had access to student loans. Since Brexit, most EU students have lost that status, and now face much higher tuition fees, comparable to those paid by other international students.

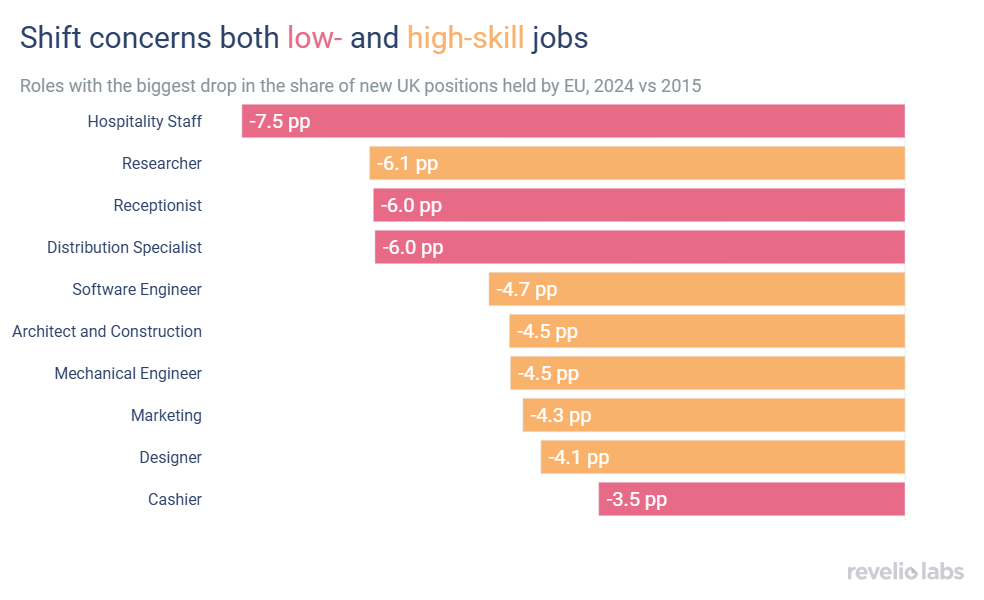

The shift away from European talent has affected both high-skilled and low-skilled roles in the UK. Compared to 2015, the share of Europeans in new positions in hospitality, retail sales, and logistics significantly declined in 2024, with drops above 6 percentage points. However, high-skilled roles such as Researcher and Software Engineer were also impacted, with their shares dropping by 6.1 and 4.7 percentage points, respectively.

Interestingly, while Brexit might have successfully reduced flows from Europe, it has not necessarily created more opportunities for UK nationals. Over the past five years, migration from other parts of the world has increased, with these individuals becoming an ever-larger part of the UK workforce. The share of new roles taken up by non-EU migrants has increased by more than 7 percentage points between 2015 and 2024, more than compensating for the drop in European representation. As a result, UK nationals now make up a smaller share of those starting new jobs compared to 2015.

In conclusion, five years after Brexit, the UK’s labor market and student body have undergone significant changes. Europeans play an increasingly smaller role, but the decline has been more than made up for by immigration from other non-EU countries. This shift toward a more global workforce presents both challenges and opportunities. On the one hand, immigration from non-EU countries may increase job competition and wage pressures in the UK, potentially creating labor market issues similar to those that originally motivated Brexit supporters. On the other hand, the influx of high-skilled talent from other parts of the world greatly boosts the UK’s global competitiveness and its ability to further attract and retain this talent will be crucial in sectors like tech, finance, and research.