Learning Disruptions During COVID Will Cost Countries Trillions

Teachers were left unprepared during COVID, and now students are failing

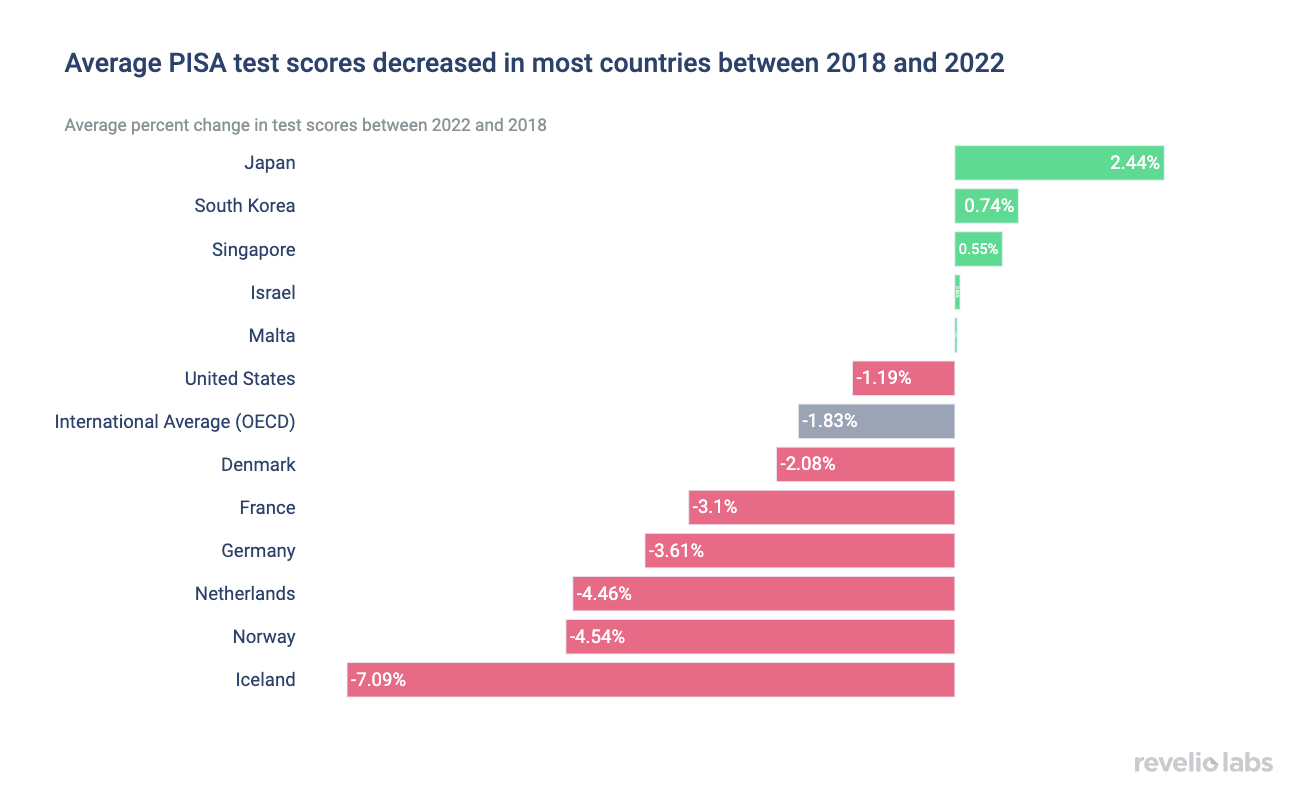

PISA test scores track 15-year-olds’ abilities in Reading, Maths, and Science across all OECD and associated countries. The latest results show that most countries saw a decline in average test scores since the previous test, a concerning trend regarding future incomes and countries’ potential for growth.

The poor performance in the 2022 tests can be attributed to lost learning time caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, which hit just as the cohort of students was being taught key concepts in the areas covered by the PISA test.

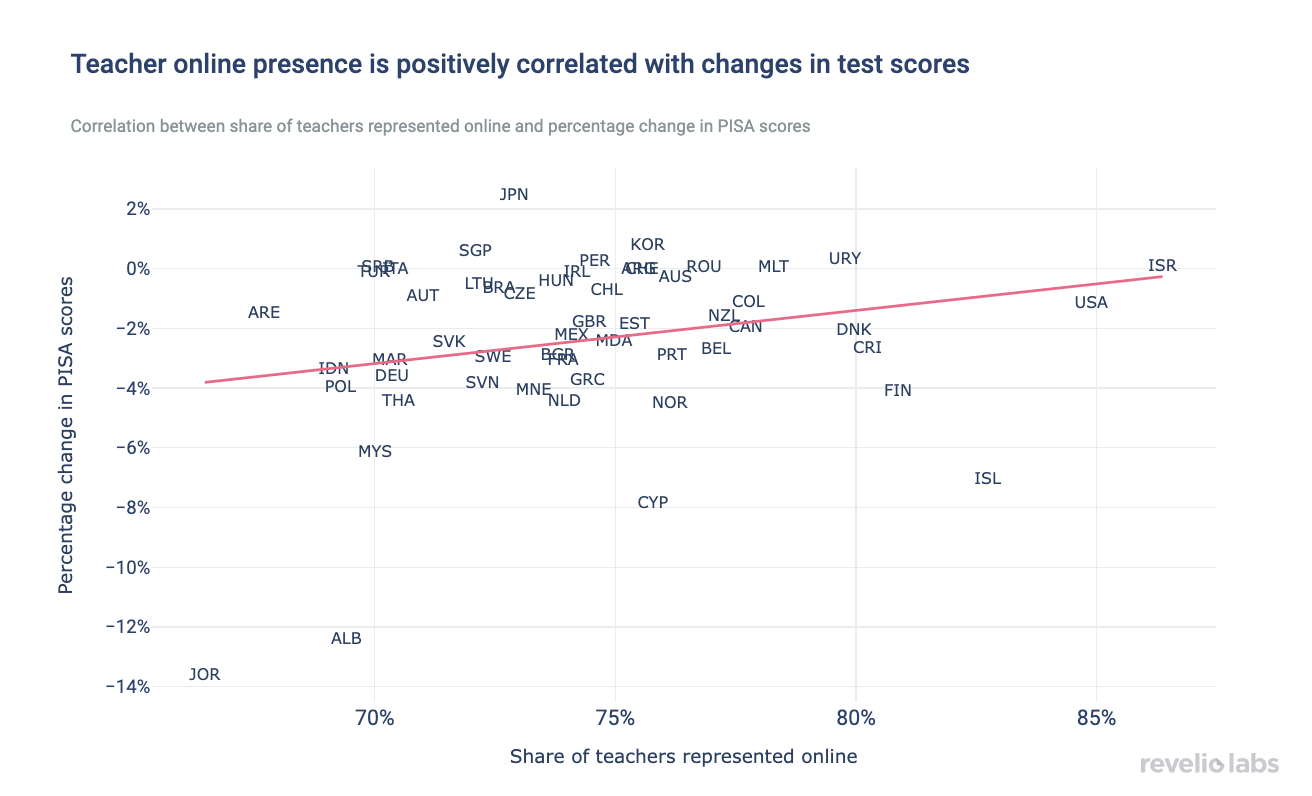

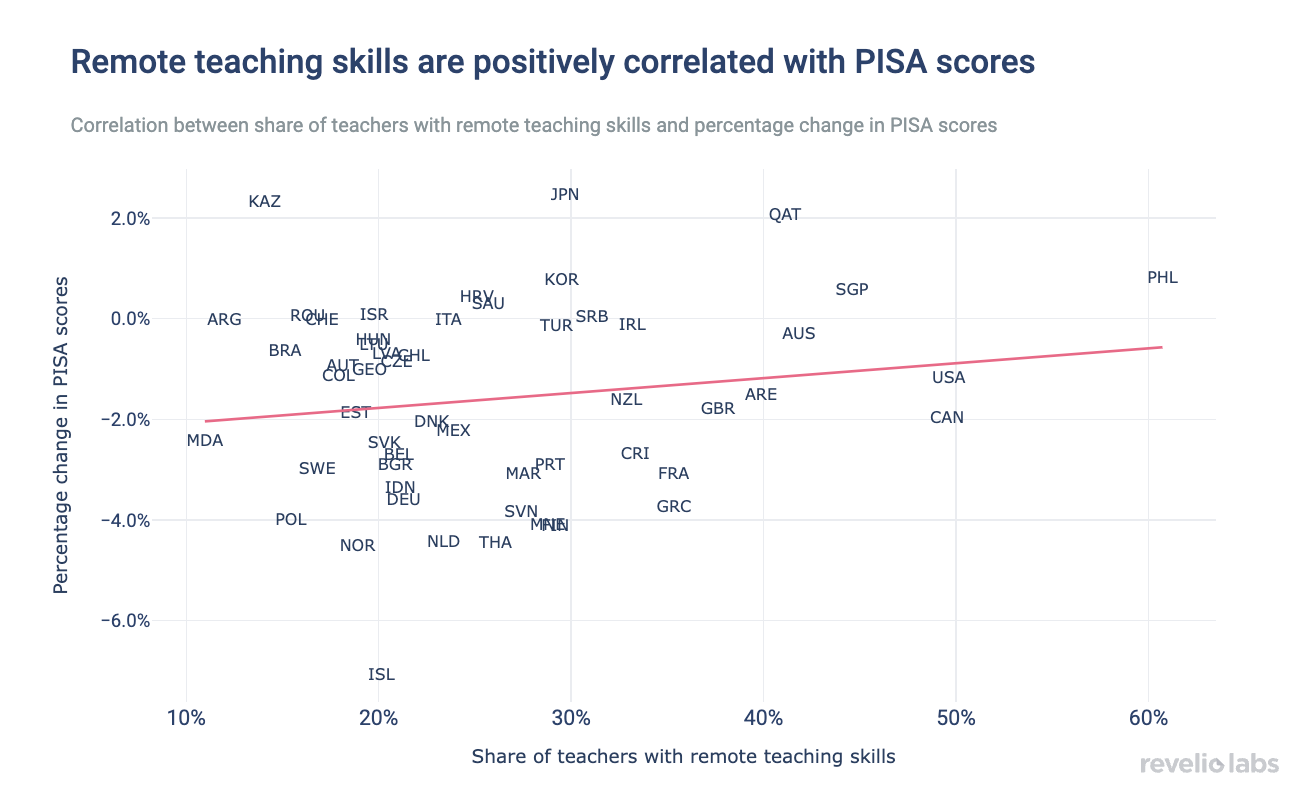

We find that changes in countries’ test scores are positively correlated with their readiness to adapt to online learning and remote schooling solutions, as measured by teachers’ remote teaching skills and online presence.

The COVID-19 pandemic caused an unprecedented disruption to everyday life. This disruption was particularly impactful for children and teenagers, causing an abrupt change to their routines and confining them to stay at home. School closures and virtual learning led to widespread challenges in education. Different countries across the world dealt with this change in various ways and adopted coping strategies at different speeds. In late 2023 the OECD published its 2022 PISA results: a test of Math, Science, and Reading comprehension of representative samples of 15-year-olds across 85 countries. The results were sobering—on average scores decreased among most countries compared to the 2018 results.

While most countries’ average PISA scores, including the OECD average, decreased since the last test in 2018, a few countries like Japan, South Korea, and Singapore managed to increase their scores. The United States, like Denmark, saw only a small decline in average test scores. Countries with the greatest losses in average scores included Iceland, Norway, the Netherlands, and Germany.

The problem is that these are not just test scores, they represent the collective decline in students’ basic skills due to the disruption in schooling and the resulting loss of learning time caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. If uncorrected, this decline will have irreversible effects on students’ lifetime earnings. Hanushek et al. (2024) estimate that the average US student in school during the pandemic will lose 5-6 percent of lifetime earnings. The total economic consequences are astronomical—the US alone will lose $31 trillion in present value terms—more than a year's worth of US GDP.

Different countries had very different policies in dealing with the pandemic and showed wide variations in readiness for virtual learning. For example, in 2020, a household survey of German parents showed that students’ time spent on learning and studying had been cut in half at the beginning of the pandemic in 2020. In contrast, lost learning time was a lot less dramatic in other countries.

We want to understand the relationship between a country’s readiness for switching to a remote learning setting and its subsequent losses in PISA test scores. This relationship is heavily influenced by both the remote learning infrastructure available in the country and teachers’ preparedness to utilize it.

Sign up for our newsletter

Our weekly data driven newsletter provides in-depth analysis of workforce trends and news, delivered straight to your inbox!

We find that countries, where teachers are highly represented online and are likely to possess a professional online profile, have lower losses in test scores compared to countries with low online representations of teachers. Teachers with an online presence already have the tools and skills that allow them to switch to online teaching learning with ease. Those struggling with technology may have been more reluctant to quickly adapt to the possibility of online teaching.

Countries with the high representations of teachers online and relatively low test score losses include Israel and the US. In contrast, Germany and Poland are among the countries with lower representations and greater losses. In particular, teachers in the US are 16 percentage points more likely to have an online representation compared to Poland. The test score decreased by 1% in the US instead of 4% in Poland. For every ten percentage points greater teacher online representation, test scores decreased by 1.8 percentage points less. In a similar vein, in countries where teachers are more likely to list remote teaching skills such as Zoom, PowerPoint, or e-learning as part of their skills, test scores were relatively better in 2022.

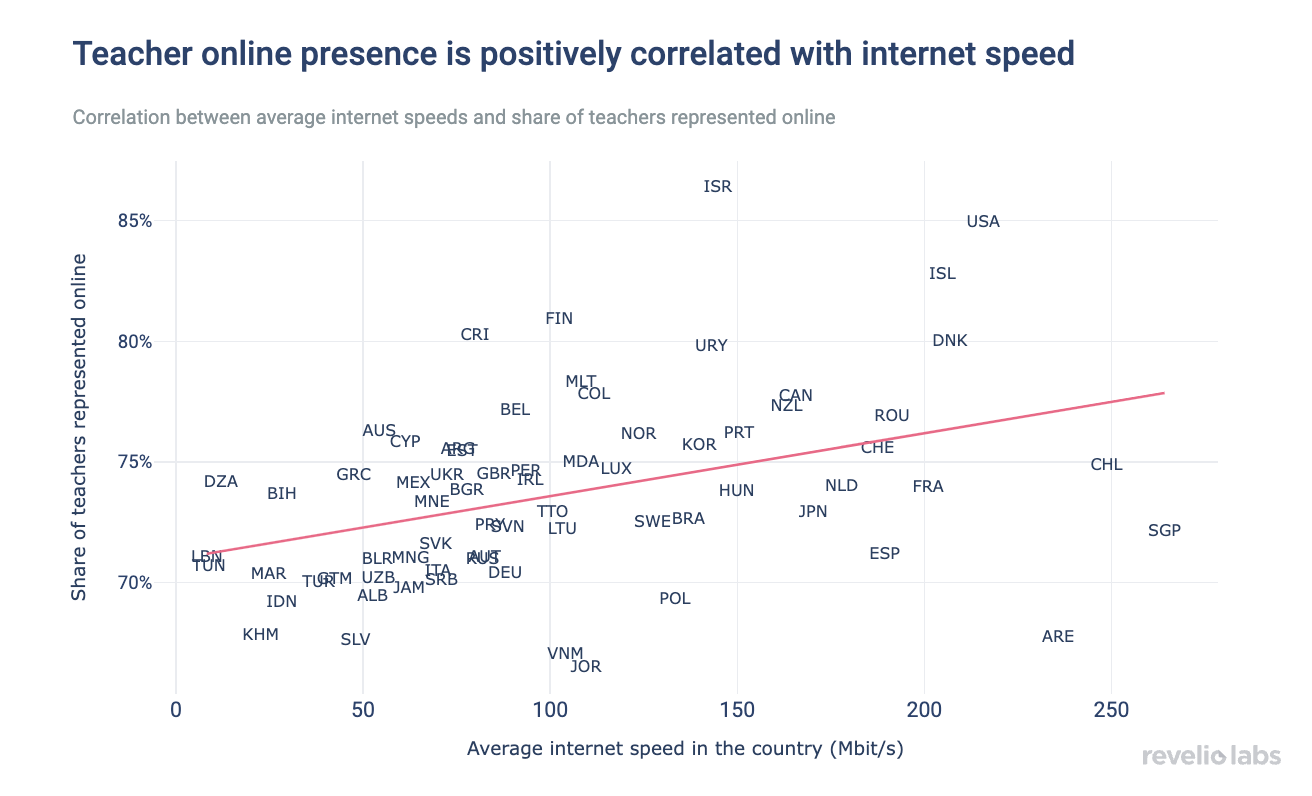

We validate our metrics for remote learning readiness by correlating them to countries' average internet speed. A country's technology infrastructure is a key determinant in how viable and efficient virtual learning solutions are. We find that both teachers' online representativeness and e-learning skills are positively correlated with the average internet speed of a country—lending further credibility to these two metrics.